Kilbonane Graveyard. |

|||||||

|

|

I have very little by way of information specifically related to Kilbonane Graveyard, for the most part what I have written here applies to most rural graveyards in Co. Cork. *********************** It is probably true that apart from the occasions when we go into a graveyard to attend the funeral of a relative or a friend or to pray at the graveside of someone who had been near and dear to us in life. Very few of us spend too much of our leisure time visiting burial grounds. It is equally true that whenever we do find ourselves within their confines we rarely devote much time to examining and admiring the memorials or reading the inscriptions upon them.

Every class and creed is represented here among the dead, lying side by side, we find Catholics, Protestants and unbelievers. Each inscription is a miniature biography, and when all are assembled together they provide the nucleus of a Parish history close on three hundred years. This site we know has been a place of worship for almost four hundred years, and possible much longer, it may well date back a thousand years. It was Pope Gregory The Great that gave permission to have graveyards, adjoining the churches, so to make it easier for people in Rome to pray for their dead, as they were complaining about the difficulty of travelling out of Rome to the Catacombs.

Extending to the southward from the old church and in conformity with the traditional arrangement that required all interments to take place on the sunny south side of the church, is the main burial area. This area was almost completely appropriated by Catholics from time immemorial and in use perhaps from early as Norman times by the same families or their recognised representatives. Throughout Europe in medieval times, the area between

the church fabric and the northern boundary wall was reserved for

open air meetings, dancing, and various kinds of sport, particularly

wrestling, ballgames and archery. But there is little evidence to

show that the graveyard was put to a similar use in Ireland. It is

significant however that Catholics very rarely used the north side

of the burial ground, there being widespread prejudice among them

against burial in the area, rooted apparently in superstition which

looked upon the cold north as a source of evil and hence regarded

it as the "wrong side". This Graveyard would be one of the

exceptions, as there are a number of graves outside the north wall.

It is quiet possible that these burial places do not date back as

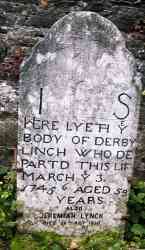

far as some of the other graves Ancient Grave Markers. The practice of marking human- burial dates back almost four thousand years. The earliest burials took place in "Wedge Graves" such as Lacthneil near Crookstown. Later large single standing stones were used to mark the place burial, which are found in many parts of the parish, such as Currabeha, Clodagh, Curraghclough and Knockboy. Between the third and seventh century, the standing stone was inscribed with Ogham writing. Following the introduction of Christianity it is believed that many of Ogham inscribed monuments were either buried under ground or irreparable damaged. In Knocknshanavee just north of Farnanes a large number of Ogham Stones were used in the construction of a souterrain, and can now be seen in the Stone Corridor in the UCC. Some survived and others had crude crosses cut into them to "christianise" them. The next step in the evolution of the Headstone was the Celtic Cross, where part of the stone was cut away and the cross remained. It is not possible the say when headstones were first used to mark graves within Churchyards, but there appears to have been widespread use of fieldstones, before headstones became common, often the stones were taken from the ruins of the old Church, which added to the destruction of many of these old buildings.

|

||||||